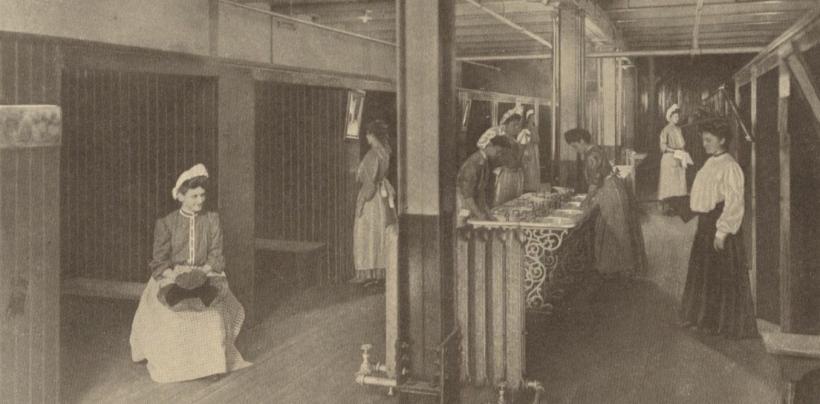

A 19th-century photograph of a women’s restroom in a Pittsburgh factory. Author provided.

These laws were adopted as a way to further early 19th century moral ideology that dictated the appropriate role and place for women in society.

For years, transgender rights activists have argued for their right to use the public restroom that aligns with their gender identity. In recent weeks, this campaign has come to a head.

In March, North Carolina enacted a law requiring that people be allowed to use only the public restroom that corresponds to the sex on their birth certificates. Meanwhile, the White House has taken an opposing position, directing that transgender students be allowed to use the bathroom that matches their gender identity. In response, on May 25, 11 states sued the Obama administration to block the federal government from enforcing the directive.

Some argue that one solution to this impasse is to convert all public restrooms to unisex use, thereby eliminating the need to even consider a patron’s sex. This might strike some as bizarre or drastic. Many assume that separating restrooms based on a person’s biological sex is the “natural” way to determine who should and should not be permitted to use these public spaces.

In fact, laws in the U.S. did not even address the issue of separating public restrooms by sex until the end of the 19th century, when Massachusetts became the first state to enact such a statute. By 1920, over 40 states had adopted similar legislation requiring that public restrooms be separated by sex.

So why did states in the U.S. begin passing such laws? Were legislators merely recognizing natural anatomical differences between men and women?

I’ve studied the history of the legal and cultural norms that require the separation of public bathrooms by sex, and it’s clear that there was nothing so benign about the enactment of these laws. Rather, these laws were rooted in the so-called “separate spheres ideology” of the early-19th century — the idea that, in order to protect the virtue of women, they needed to stay in the home to take care of the children and household chores.

In modern times, such a view of women’s proper place would be readily dismissed as sexist. By highlighting the sexist origin of laws mandating sex-separation of public restrooms, I hope to provide grounds for at least reconsidering their continued existence.

The rise of a new American ideology

During America’s early history, the household was the center of economic production, the place where goods were made and sold. That role of the home in the American economy changed at the end of the 18th century during the Industrial Revolution. As manufacturing became centralized in factories, men left for these new workplaces, while women remained in the home.

Soon, an ideological divide between public and private space arose. The workplace and the public realm came to be considered the proper domain of men; the private realm of the home belonged to women. This divide lies at the heart of the separate spheres ideology.

The sentimental vision of the virtuous woman remaining in her homestead was a cultural myth that bore little resemblance to the evolving realities of the 19th century. From its outset, the century witnessed the emergence of women from the privacy of the home into the workplace and American civic life. For example, as early as 1822 when textile mills were founded in Lowell, Massachuetts, young women began flocking to mill towns. Soon, single women constituted the overwhelming majority of the textile workforce. Women would also become involved in social reform and suffrage movements that required them to work outside the home.

Nonetheless, American culture didn’t abandon the separate spheres ideology, and most moves by women outside the domestic sphere were viewed with suspicion and concern. By the middle of the century, scientists set their sights on reaffirming the ideology by undertaking research to prove that the female body was inherently weaker than the male body.

Armed with such “scientific” facts (now understood as merely bolstering political views against the emergent women’s rights movement), legislators and other policymakers began enacting laws aimed at protecting “weaker” women in the workplace. Examples included laws that limited women’s work hours, laws that required a rest period for women during the work day or seats at their work stations, and laws that prohibited women from taking certain jobs and assignments considered dangerous.

Midcentury regulators also adopted architectural solutions to “protect” women who ventured outside the home.

Architects and other planners began to cordon off various public spaces for the exclusive use of women. For example, a separate ladies' reading room — with furnishings that resembled those of a private home — became an accepted part of American public library design. And in the 1840s, American railroads began designating a “ladies' car” for the exclusive use of women and their male escorts. By the end of the 19th century, women-only parlor spaces had been created in other establishments, including photography studios, hotels, banks and department stores.

Sex-separated restrooms: putting women in their place?

It was in this spirit that legislators enacted the first laws requiring that factory restrooms be separated by sex.

Well into the 1870s, toilet facilities in factories and other workplaces were overwhelmingly designed for one occupant, and were often located outside of buildings. These emptied into unsanitary cesspools and privy vaults generally located beneath or adjacent to the factory. The possibility of indoor, multi-occupant restrooms didn’t even arise until sanitation technology had developed to a stage where waste could be flushed into public sewer systems.

But by the late-19th century, the factory “water closet” — as restrooms were then called — became a flashpoint for a range of cultural anxieties.

First, deadly cholera epidemics throughout the century had heightened concerns over public health. Soon, reformers known as “sanitarians” focused their attention on replacing the haphazard and unsanitary plumbing arrangements in homes and workplaces with technologically advanced public sewer systems.

Second, the rapid development of increasingly dangerous machinery in factories was viewed as a special threat to “weaker” female workers.

Finally, Victorian values that stressed the importance of privacy and modesty were subjected to special challenge in factories, where women worked side by side with men, often sharing the same single-user restrooms.

It was the confluence of these anxieties that led legislators in Massachusetts and other states to enact the first laws requiring that factory restrooms be sex-separated. Despite the ubiquitious presence of women in the public realm, the spirit of the early century separate spheres ideology was clearly reflected in this legislation.

Understanding that “inherently weaker” women could not be forced back into the home, legislators opted instead to create a protective, home-like haven in the workplace for women by requiring separate restrooms, along with separate dressing rooms and resting rooms for women.

Thus the historical justifications for the first laws in the United States requiring that public restrooms be sex-separated were not based on some notion that men’s and women’s restrooms were “separate but equal” — a gender-neutral policy that simply reflected anatomical differences.

Rather, these laws were adopted as a way to further early 19th century moral ideology that dictated the appropriate role and place for women in society.

The future of public restrooms

It is therefore surprising that this now discredited notion has been resurrected in the current debate over who can use which public restrooms.

Opponents of transgender rights have employed the slogan “No Men in Women’s Bathrooms,” which evokes visions of weak women being subject to attack by men if transgender women are allowed to “invade” the public bathroom.

In fact, the only solid evidence of any such attacks in public restrooms are those directed at transgendered [sic] individuals, a significant percentage of whom report verbal and physical assault in such spaces.

In the midst of the current maelstrom over public restrooms, it is important to keep in mind that our current laws mandating that public restrooms be separated by sex evolved from the now-discredited separate spheres ideology.

Whether or not multi-occupancy, unisex restrooms are the best solution, our lawmakers and the public need to begin envisioning new configurations of public restroom spaces, ones far more friendly to all people who move through public spaces.

Terry S. Kogan, Professor of Law, University of Utah

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.